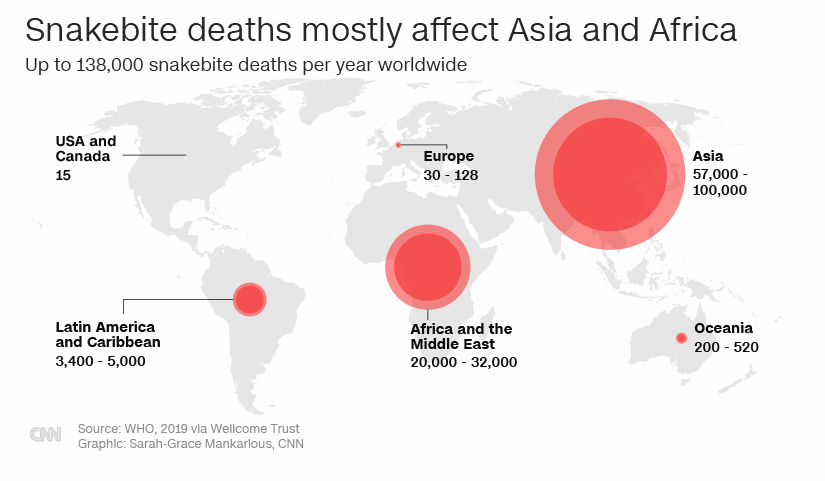

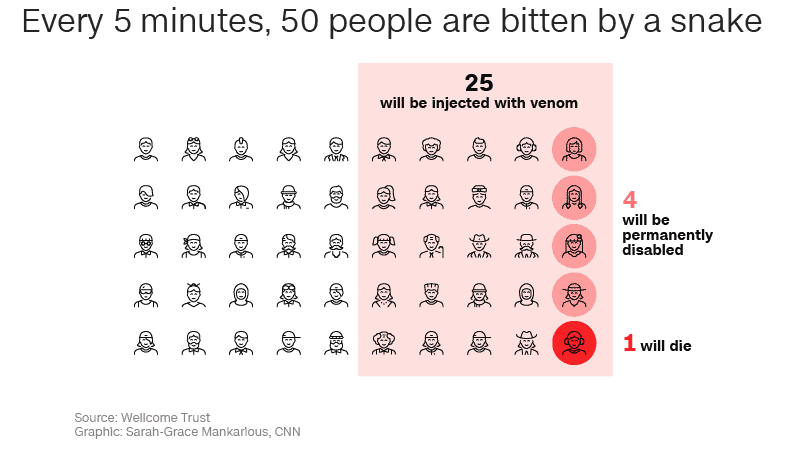

Ophidiophobia is the term to describe one’s abnormal fear of snakes. Researchers believe that the fear has evolutionary traces, developed by early humans as a survival tactic. Although the exact number of individuals suffering from Ophidiophobia is unknown, snake fears are relatively common. Considering that 200 people die every day from snakebites around the world, perhaps the phobia is understandable, if not justified. To paint an even more alarming picture, of the estimated entire human population of 7.3 billion (2019 census), 5.8 billion people are currently at risk from encountering a venomous snake. Of that number, 7,400 people are bitten every day, and between 81,000 – 138,000 deaths occur every year because of snake bites.

Snakebite envenoming (poisoning from snake bites) is an infectious disease that occurs from the dangerous mix of venoms from a snakebite. Bites can cause paralysis, blood disorders, kidney failure, and complete tissue impairment that can lead to amputation.

The Challenge With Anti-Venom Treatments

Many serious health consequences and death from snake bites can be prevented through proven anti-venom treatments, but those treatments only account for 60% of the world’s venomous snakes. And in Africa, where injury from bites are the most abundant, the treatment is considered only 10% effective from local snakes. This major issue, along with the high cost of the treatment, and other socioeconomic factors, create a challenge for global and regional health organizations especially in areas where the probability of snake bites is high and the quality medical infrastructure is low. And of the individuals most likely to experience a bite in those areas? According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “rural cropping and livestock workers, hunters/gathers and their children are among the most affected [by snake bites].” Young children can experience a more severe injury from a bite due to their smaller body mass.

World Health Organization’s Strategy for Prevention and Control

In response to what has become a dire need for action, the WHO announced last week its four-part strategy to combat what is being called “a global hidden health crisis.” WHO’s overall objective is to decrease the number of disabilities and deaths from snakebites worldwide by 50% before 2030. To do so, WHO has invested $136 million to go towards educating communities about what to do in case of a snakebite, making treatment more widely available and accessible, strengthening inadequate national health systems, and increasing partnerships, medical coordination, and healthcare resources at a regional level.

The vast majority of serious injury and death from snakebites happen in parts of Africa and Asia (home to two of the most dangerous and deadly snakes: saw-scaled viper and Russell’s viper) and countries within those regions will be the initial recipients of WHO’s technical support and campaign initiatives.

What To Do In Case Of A Snakebite

In the United States, there are 20 venomous snakes, 16 of which are rattlesnakes. The eastern diamondback rattlesnake and the western diamondback rattlesnake are identified as causing the most fatalities.

In case of a snakebite, our partners at Cleveland Clinic recommend:

- Seek medical attention as quickly as possible.

- Apply first aid treatment

- Remove any jewelry or watches, as these could cut into the skin if swelling occurs.

- Keep the area of the bite below the level of the heart to slow the spread of venom through the bloodstream.

- Remain still and calm. Moving around will make venom spread faster through the body.

- Cover the bite with a clean, loose-fitting, dry bandage.

- The main goal is to administer the correct antivenom as soon as possible. Knowing the size, color and shape of the snake can help determine the best treatment for a bite.