School is out and summer is in full swing. Days are filled with backyard barbecues, time with friends, and dips in the pool to beat that relentless summer heat. Though swimming in community pools is a regular part of many American’s summer routines, federal public health officials are urging people to think twice before diving in.

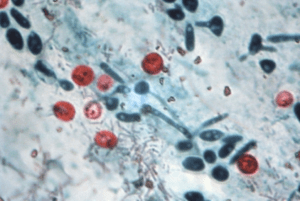

A few weeks ago, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report warning of the increased number of outbreaks linked to a parasite known as Cryptosporidium. Cryptosporidium causes cryptosporidiosis (both also commonly known as “crypto” for short) and is the leading cause of outbreaks of diarrhea linked to water in the United States. The newly released publication tracked cryptosporidiosis outbreaks in the US from 2009 to 2017. During that time period, there were 444 reported outbreaks that totaled 7,465 cases in 40 states. Though rarely fatal, of these, nearly 300 individuals required hospitalization. The CDC found that recreational water was the most common source, linked to 35.1% of the outbreaks and 56.7% of the cases. The scariest part of the report? Research has indicated that cryptosporidiosis outbreaks have continued to increase by an average of 13% per year.

Transmission and Symptoms

The parasite most commonly affects the small intestine. Symptoms of crypto include watery diarrhea, stomach pain and cramps, nausea, vomiting, and fever. Prolonged illness could lead to dehydration and weight loss. For the average person, symptoms usually last one to two weeks. The parasite is of particular concern to people with weakened immune systems. These individuals could develop serious, chronic, or sometimes even fatal illness if the parasite affects other areas of the digestive or respiratory tract.

Unfortunately, when humans share the same body of water, they often also share germs. Though most of these germs are killed by chlorine, crypto is protected by an outer shell and has an extremely high tolerance to the germ-killing agent. This means it can survive in a pool for up to seven days. Crypto can also remain alive in saltwater for several days, so polluted ocean water may also pose a risk. Infected people or animals defecate cysts containing the parasite. In pools, the parasite can enter the body when a swimmer swallows contaminated water. Once multiplied in a new host’s gastrointestinal or respiratory system, the parasite will often begin to cause symptoms. The new host will also begin to defecate the parasite and will continue the spread of disease unless precautions are taken.

Prevention

The CDC sees the highest number of crypto cases during the summer as temperatures rise and public pool usage increases. To prevent the spread of disease in pools, the CDC recommends that anyone suffering from diarrhea, including children, wait at least two weeks after symptoms subside before swimming. If you come into contact with a human or animal that you suspect to have the parasite, clean affected areas with hydrogen peroxide since regular chlorine bleach will not work. Finally, the CDC’s best advice to protect yourself at the pool? Shut your mouth. Healthy swimmers should do their best to avoid swallowing water to dodge any of the summer-time germs, including crypto, lurking in public pools.