The Situation in Los Angeles

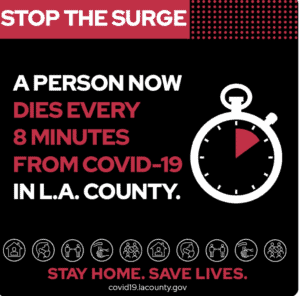

Yesterday was the single deadliest day of the pandemic with 4,000 deaths, and nowhere is harder hit than Los Angeles County. Cases have spiked drastically since December, with 809,052 cases and 10,739 deaths. Deaths were occurring every 8 minutes yesterday. The California Department of Health rates LA county as Tier 1: Widespread risk. The seven-day daily average test positivity rate sits at 21%, far higher than the optimal 5%. These ratings indicate that LA County’s testing capacity is far below what is necessary to keep up with the spread of COVID-19.

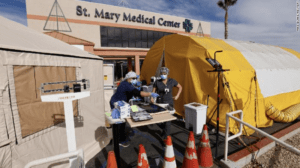

The surge in cases is pushing the county’s’ already strained healthcare system to the brink. As of January 5, 8,098 COVID-19 patients are in Los Angeles County hospitals. And as of January 7, there are 1,628 patients in ICUs, and only 313 ICU beds are available, the lowest since March. Other issues affecting COVID-19 care emerged, including problems with oxygen supplies. These circumstances have forced public health officials to modify standard operating procedures related to oxygen administration and emergency services to conserve resources.

The surge in cases is pushing the county’s’ already strained healthcare system to the brink. As of January 5, 8,098 COVID-19 patients are in Los Angeles County hospitals. And as of January 7, there are 1,628 patients in ICUs, and only 313 ICU beds are available, the lowest since March. Other issues affecting COVID-19 care emerged, including problems with oxygen supplies. These circumstances have forced public health officials to modify standard operating procedures related to oxygen administration and emergency services to conserve resources.

Impact on Emergency Medical Services

To conserve vital hospital resources, the Emergency Medical Services Agency of Los Angeles issued a directive on January 4 that “adult patients in blunt- traumatic and nontraumatic out-of-hospital cardiac arrest shall not be transported if return of spontaneous circulation is not achieved in the field.” Effectively, LA-based ambulances and EMS services will not transport patients to hospitals if they cannot get a pulse during resuscitation on the field.

The new policy is a significant indicator of the situation in LA. The medical system is strained and unable to enact additional measures to help severe patients. However, this directive is not a significant shift from the current policy of resuscitating in the field. Lifesaving measures will continue for all cardiac patients. The new directive will require paramedics to consult with physicians in the hospital to determine if revival attempts are futile and, therefore, terminate resuscitation on the scene.

Strained Oxygen Supply

Treating severe COVID cases requires oxygen, and the surge in cases is causing a significant strain on the oxygen supplies. The diminishing supply is now pushing hospitals and EMS to conserve oxygen. In another directive, also issued on January 4, the LA County Emergency Medical Agency asked ambulance crews to only administer oxygen to those whose oxygen saturation levels are below 90%; normal oxygen levels are between 95-100%.

The oxygen demand has increased for other reasons too – including suboptimal or insufficient equipment. Oxygen is stored in liquid form at -300F. and the increased flow of oxygen caused the vaporization equipment to freeze, further restricting the supply. Severe frozen pipes are more likely to occur in hospitals with converted ICU beds. Regular hospital beds have smaller lines to transport oxygen, freezing more easily – forcing hospitals to rely on large gas tanks to supply oxygen to those beds.

There are efforts in place to increase the oxygen supply immediately. As part of a state “Oxygen Task Force,” the Army Corps of Engineers is updating oxygen delivery systems at six older hospitals in LA County: Adventist Health White Memorial Hospital, Los Angeles; Emanate Health Queen of the Valley Hospital, West Covina; Mission Community Hospital, Panorama City; Beverly Community Hospital, Montebello; Lakewood Regional Medical Center, Lakewood; PIH Health Hospital, Downey.

As part of the larger Department of Defense operation to support civil authorities, combat medics, nurses, respiratory therapists, and other support staff are aiding LA County-USC Medical Center and Harbor-UCLA Medical Center.

Effect on Surrounding Areas

Surrounding counties of Kern, San Bernardino, Orange, and Ventura are experiencing similar healthcare system strains. Wait times for admission vary and can be for multiple hours. In Orange County, field hospitals are in use to handle non-ICU cases. Providers may not be able to provide the same level of personal or individualized care.

Where next?

Oxygen shortage and overburdened medical systems are not unique to LA County hospitals. Hospitals in the Navajo Nation observed the flow of oxygen weaken in their facilities as their medical system were not able to handle the influx of patients requiring oxygen. The infrastructure of rural, smaller, or older hospitals may not be able to handle an increase in cases.

Other metropolitan areas are experiencing strain, including Dallas- Ft. Worth. On January 5, there were 11 available ICU beds in Dallas County, 14 in Tarrant County, five in Collin County. These counties have a combined population of 5.6 million people. President and CEO of the DFW Hospital Council, Stephen Love, stated: “This is very serious and a critical situation.”

Health experts fear a more considerable spike in COVID-19 cases in January resulting from holiday gatherings and travel. Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer stated, “We’re likely to experience the worst conditions in January that we’ve faced the entire pandemic.” This spike is likely to continue to stress the LA county system and force hospitals in both rural and metropolitan areas to take similar measures to conserve resources.