A series of Marburg outbreaks in Africa have raised concerns about the potential future spread of this deadly disease and how that, in turn, might affect public health in nations around the world. With two outbreaks of the Marburg virus currently ongoing in two parts of Africa, there is a reasonable cause for worry.

What is Marburg Disease?

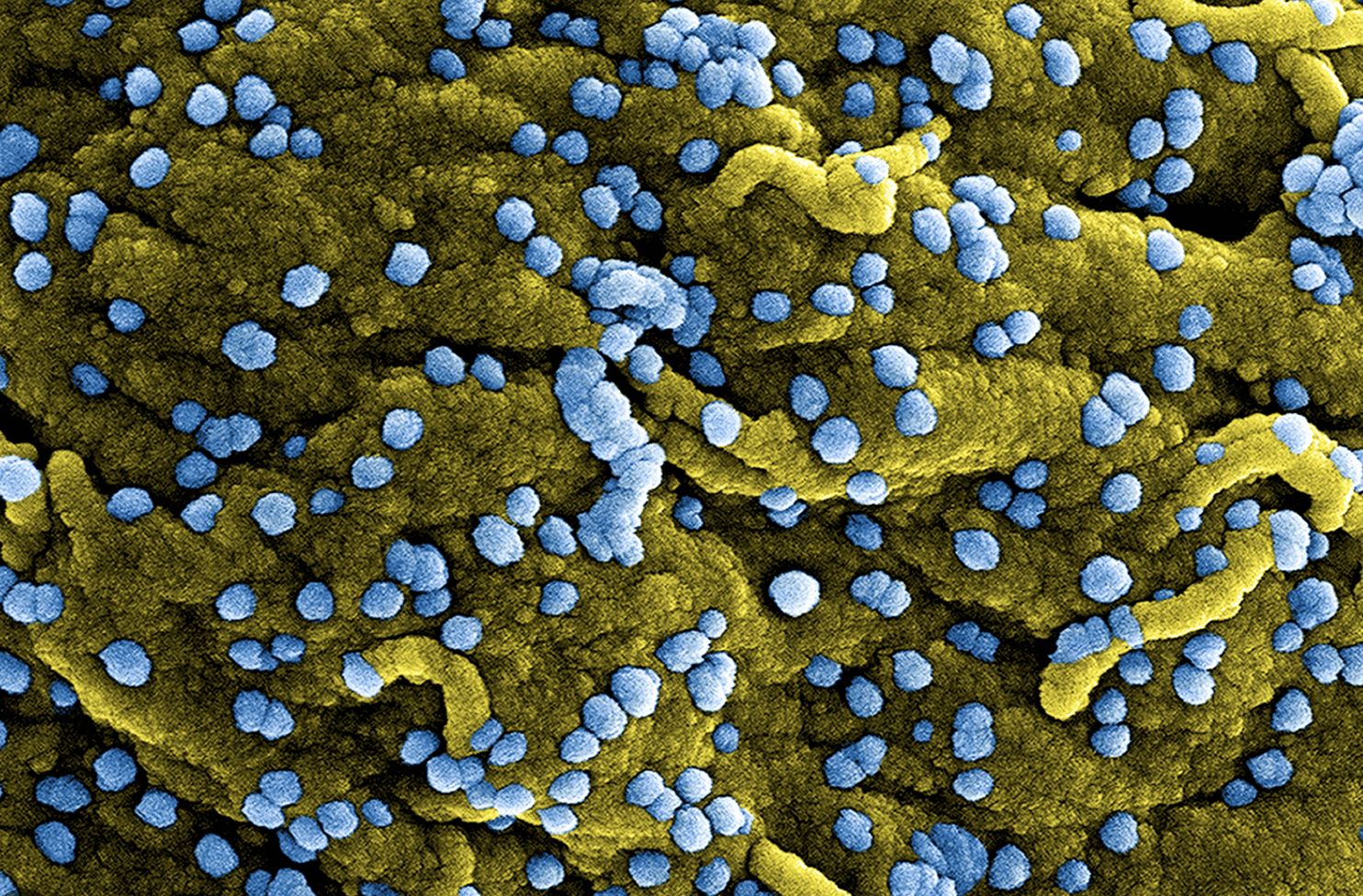

First identified in 1967 when separate outbreaks occurred in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and Belgrade, Serbia, Marburg disease is a member of the Filoviridae family of virii, including Ebola and other hemorrhagic diseases. While primates–including humans–are particularly susceptible to Marburg, the Egyptian fruit bat is a vector of transmission to humans. Marburg follows a set of clinical phases similar to Ebola: after an incubation period averaging 5 to 9 days, patients infected with Marburg virus start to exhibit some combination of the following symptoms: a high fever accompanied by chills, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pharyngitis, rash, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis, and malaise.

These initial symptoms last for roughly a week–typically Day 1 to Day 5– before progressing to more serious organic forms, including respiratory problems, edema, and the beginnings of hemorrhagic issues in various forms lasting up to roughly Day 13. Patients in this phase may start to exhibit aggression or anger. After Day 13, patients’ paths separate into those survivors and fatal cases, with two different constellations of symptoms. Survivors will experience muscle weakness, myalgia/fibromyalgia, hepatitis, ocular issues, and psychosis. Fatalities will exhibit increased mental confusion, sustained fever, convulsions, and coma. Coagulopathy and hemorrhaging will continue until death. In both sets of patients, this phase lasts from Day 13 up to around Day 21.

Ongoing Marburg Outbreaks

There are two known outbreaks of Marburg, both in sub-Saharan Africa. An outbreak in Tanzania is coming to a close, with only a handful of individuals left in quarantine. However, on the other side of the continent, an outbreak in Equatorial Guinea is ongoing, with the World Health Organization voicing concerns about governmental transparency in reporting new cases. Ten confirmed deaths have been reported.

The future path of this round of outbreaks is challenging to predict. As WHO notes regarding Marburg, “the trajectory of outbreaks is uncertain.”

Treatment and Diagnosis of Marburg

There are no vaccines or antiviral treatments for Marburg disease, although there are several promising possibilities in the trials phase at the time of this writing. Diagnosing Marburg disease can be likewise tricky–it is clinically nearly identical to Ebola–although several options do exist:

- antibody-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen-capture detection tests

- serum neutralization test

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- electron microscopy

- virus isolation by cell culture

Diagnosis is a critical function in both limiting the spread of Marburg and advancing research in treating and preventing the disease.

On the subject of treatment, in the absence of pharmaceutical therapies, supportive care is the best approach. This may include any combination of the following:

- Minimizing invasive procedures, including injections and IVs

- Preventing dehydration via fluids and electrolytes

- Administration of anticoagulants early in infection to prevent DIC

- Administration of procoagulants late in infection to counter hemorrhaging

- Maintaining oxygen levels

- Pain Management

- Antifungals or antibiotics to treat secondary infections

These supportive treatments have been shown to increase the patient’s chance of survival and to speed recovery in those who do survive.

Preventing and Controlling Marburg Disease

Controlling Marbug begins with the prevention of transmission. Towards that end, the Centers for Disease Control recommends the following measures to those working, living, or traveling in areas that may be affected by the Marburg virus:

- Avoid contact with blood and body fluids (such as urine, feces, saliva, sweat, vomit, breast milk, amniotic fluid, semen, and vaginal fluids) of people who are sick

- Avoid contact with semen from a person who has recovered from Marburg until no traces are present

- Avoid contact with items that may have come in contact with an infected person’s blood or body fluids

- Avoid funeral or burial practices that involve touching the body of someone who died from suspected or confirmed Marburg

- Avoid contact with fruit bats and nonhuman primates (such as monkeys and the blood, fluids, or raw meat prepared from these or unknown animals. Also, avoid areas known to be inhabited by fruit bats (such as mines or caves)

While Marburg is a concern and future outbreaks are difficult to predict, there is no cause for broader alarm. Avoiding travel to impacted areas, following the above guidelines, and staying informed about the potential future spread of Marburg are our collective best courses of action.