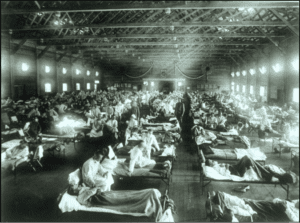

2018 marks the 100th anniversary of an influenza pandemic that devastated the world, a global outbreak that has been cited as the worst in recorded history. As American troops deployed to the Western Front at the close of World War 1, the flu spread from Kansas military camps across the United States and Europe. The disease, known as “Spanish Flu” after newspapers reported a serious case in the king of Spain, spread deep into victims’ lungs, causing pneumonia and severe bleeding that could kill in a matter of hours. Cities became ghost towns as terrified citizens hid from the contagion. In one year, between 50 and 100 million people died – more than all the combat deaths in World War I itself.

Now medical and infectious disease experts warn that the next flu pandemic could be even more devastating – and even 100 years later, we may not have the tools to stop it.

The keystone problem of flu pandemic preparedness is outdated, slow-moving immunization technology. Today’s main flu vaccines take five to six months to manufacture, and they cover only the few strains that World Health Organization models predict will spread widely. It is likely that vaccines for new virulent strains would arrive too late to protect millions from fast-mutating, highly infectious variants like the Spanish flu.

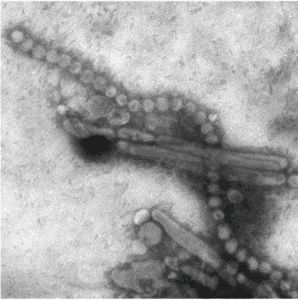

Researchers hope that the development of new “super-shot” vaccines could prevent pandemics by immunizing against multiple flu strains for five or even ten years. These new vaccines would modify non-mutating proteins most flu strains share, maximizing the body’s natural immune response against any flu strains that might develop. Early studies suggest such “super-shots” could immunize against 88% of influenza A variants, dramatically improving protection. Further, vaccines based on these new techniques could be manufactured much faster, improving public health reaction time in a pandemic.

The current flu season illustrates the damage that even “normal” influenza strains can cause. Flu is spreading rapidly and hospitalizing large numbers around the world, from North America to North Africa and from Europe to China. Business analysts project over $9 billion in productivity losses to American companies this season as over 11 million workers fall ill. This season’s dominant H3N2 strain causes worse sickness with more complications than other flu variants, and vaccines only reduce H3N2 risk by 32% at best. Moreover, the season still seems to be worsening. The first two weeks of 2018 brought a dramatic rise in case counts, with 17 of 30 pediatric deaths this season occurring since New Year’s and over 2,500 flu-related hospitalizations occurring in one week alone.

Yet the ills of seasonal flu are dwarfed by the harms of pandemic influenza. Flu pandemics come from contagious new strains to which few populations are immune. If a deadly avian flu strain like China’s H7N9 mutated to spread easily from person to person, air travel and international trade would quickly carry it around the globe. The impact of a pandemic that deadly in the densely urbanized world of 2018 could dwarf the effects of 1918’s Spanish flu. For now, that nightmare scenario is just a fever dream. Yet without committing to strengthened vaccine research and funding, the world may soon wake to find the nightmare all too real.