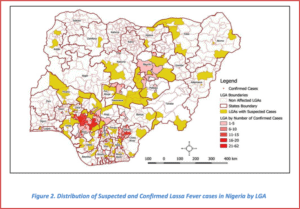

Though Nigeria escaped the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak relatively unscathed, the country is suffering through the latest Lassa fever outbreak. Since the beginning of 2018, the Nigerian Center for Disease Control has reported 353 confirmed cases across 18 of Nigeria’s 36 states, with a case fatality rate among confirmed and probable cases of 23.8%.

What is Lassa Fever?

Though Lassa fever is largely unknown in the United States, the viral illness causes an estimated 5,000 deaths per year in western Africa. Lassa is animal-borne and spread by the multimammate rat, which is endemic to the region and excretes the virus through its urine and feces. People can become infected through ingestion or inhalation of rodent urine or droppings, commonly from eating contaminated food, touching soiled objects, or inhaling small fecal particles spread in the air from sweeping. Once infected, patients experience fever, malaise, weakness, and headache, though about 20% of patients develop hemorrhagic fever and organ failure, which can be fatal. The CDC estimates that between 15-20% of people who are hospitalized because of Lassa fever will die from the illness and its complications.

Though Lassa fever is largely unknown in the United States, the viral illness causes an estimated 5,000 deaths per year in western Africa. Lassa is animal-borne and spread by the multimammate rat, which is endemic to the region and excretes the virus through its urine and feces. People can become infected through ingestion or inhalation of rodent urine or droppings, commonly from eating contaminated food, touching soiled objects, or inhaling small fecal particles spread in the air from sweeping. Once infected, patients experience fever, malaise, weakness, and headache, though about 20% of patients develop hemorrhagic fever and organ failure, which can be fatal. The CDC estimates that between 15-20% of people who are hospitalized because of Lassa fever will die from the illness and its complications.

Current Situation

The 2018 outbreak in Nigeria has reached 353 confirmed cases, including 16 healthcare workers. Laboratory testing and medical treatment for patients is concentrated in a small number of regional facilities and have been supported by international organizations to shore up testing capabilities and patient care. In addition to Nigeria, single cases have been reported in both Ghana and Liberia. Historically, disease surveillance in the region has been poor, and there may additional cases which have not been documented by public health authorities.

Outbreak Outlook

As the dry season comes to an end, the case counts are expected to decline and the outbreak will come to an end. In the long term, Lassa fever outbreaks are likely to continue in the region, as they tend to affect more rural areas, which are more difficult to access and generally lack funding. Western African countries require additional public health funding, an increase in reliable testing facilities, and improved public health access to rural and difficult-to-access communities in order to respond to future outbreaks.